On this island things fidget.

Even history.

The landscape does not sit

willingly

as if behind an easel

holding pose

waiting on

someone

to pencil

its lines, compose

its best features

or unruly contours.

Landmarks shift,

become unfixed

by earthquake

by landslide

by utter spite.

Whole places will slip

out from your grip.

‘What the Mapmaker Ought to Know’ by Kei Miller

Environmental devastation in what we now call the Caribbean is traced to colonialism's arrival. The British, Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish and French massacred indigenous populations, turned their brutal ingenuity to Africa for chattel slavery, held on to Africa and added Asia as a source for indentured labourers post-Emancipation, uprooted and transported flora and fauna from across the world for this new genesis. Of the Europeans, the British had the largest impact on Jamaica in the establishment of if its monocultural plantation, its exploitative logging that led to the near extinction of our mahogany forests before the 20th century. They played an outsized role in creating a dehumanising, rapacious global economic system that warped our relationship with ourselves and environment.

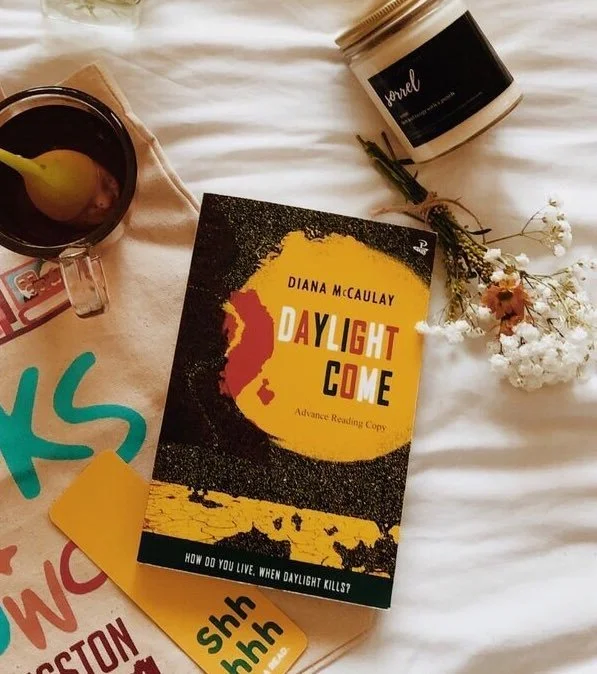

Diana McCaulay, a Jamaican white creole writer and well-known environmental activist, wrote Daylight Come (2020), published by Peepal Tree Press. A speculative climate fiction novel, McCaulay imagined what climate disaster might look like in a fictional Caribbean island named Bajacu in 2084.

Interviewed for Rebel Women Lit’s “Like a Real Book Club” podcast, Jherane Patmore asked her to talk about her research. There were such "strong cultural identities within the book...How much was from your own imagination?"

McCaulay: "A lot was from my own imagination. I felt very free to imagine what I wanted to because I wasn't setting it in the present. And, maybe you noticed, it's set…I imagined a post-racial world, so everybody has become brown. I wanted that, where the subject of a Caribbean book was not about race, and it was not a sort of underlying driving force or theme or whatever. So, I've imagined a post-racial world, and I imagined everybody speaking in a kind of, with a few sort of different non-English words thrown in, but a sort of standard English type of narrative.”

I found this to be such a curious answer. She took her novel’s title from a Jamaican folk song entitled “Day-O” alternatively known as “The Banana Boat Song”. Harry Belafonte, an African-American singer and civil rights activist born to Jamaican parents, popularised the song. Its call and response pattern is prominently associated with Africa and the African diaspora. The lyrics describe the dock workers routine, a largely Black labour force connected to the next big crop in the Americas after sugar cane - banana. Banana arguably has a more storied history for us now than sugar cane, from its early days in the late 19th century as a money earning path for the formerly enslaved population to the United States’ successful lobbying efforts to end the protective trade agreement between European and Caribbean countries to increase the overwhelming advantage its own multinational corporations’ Latin America banana plantations in the late 20th century already had. How McCaulay wrote the USA, the region’s next big colonizer, into the novel cinched in the reference perfectly.

Besides that, there was the book cover colour design incorporating both the Jamaica national flag and reggae colours; the Taino name places; much of the food, like breadfruit which the English Captain William Bligh brought from Tahiti to the Caribbean in the late 18th century; the Kingston landmark. Even the terrain that Bibi and Sorrel, the novel's mother-daughter pair, travel through read quite obviously as St. Andrew to me, complete with a denouement at the Jamaica Defence Force's Newcastle camp reimagined as the base for self-styled militaristic dictator.

Everything I have listed here is inextricably connected to how race operates in our part of the world. Unlike some, I am not against the idea of attempting "post racial" worldbuilding. However, to execute this with any kind of narrative persuasiveness would require a careful fabulation that did not rely on so many elements whose essential meanings are tied to it which then called attention to those left out. How preposterous to assert that a time leap a mere sixty odd years into future, brown colouring and “Standard English” could amount to anything approaching a narrative post racial tool kit.

David Naimon interviewed Isaac Yuen, a Hong-Kong Canadian author "with a lifelong passion for the environment", for his Between the Covers podcast as part of the “Crafting with Ursula” series. Naimon invites writers to discuss their work, in conversation with Ursula K. Le Guin, an author noted for how her speculative writing addressed race, gender, and the environment. Naimon and Yuen discussed a speculative kind of storytelling that reversed the usual dynamic in nature writing where the human "ruminates on nature". Yuen called it "reverse bridging": a narrative written from a non-human's perspective. He acknowledged its ultimate impossibility, but he delighted in the experimental generative possibilities, what could be learned from failure.

Diana McCaulay did not do the same. She did not acknowledge the “bumborassity” in a Jamaican white creole author attempting such a creative project, made more egregious by its meagerly woven veil of pretense that it was not set in Jamaica, that "brown" is devoid of racial meaning (here of all places). If she had, the tenuous "post racial" illusion would shatter…for her.

The earnest self-deception could only result in narrative confusion. Language undermined McCaulay’s feeble worldbuilding at every turn. Within the very word “Caribbean” lie variegated racial, ethnic, linguistic, national histories. Most sources trace the word’s origins to “Caribe”, a Spanish word to denote the Kalinago, one of the region’s indigenous peoples. Her pairing of “post racial” with a “standard English” was revealing. She had to spurn Patwa—to avoid its obvious West African lineage. But English is not a neutral language, not in England much less in the Caribbean. The attempt to superimpose Taino names on the landscape read as an empty, hippy dippy gesture devoid of substance. How could I read it as any kind of just restoration when it resulted in the complete erasure of Black recreation in slavery’s wake?

Give him time and he will learn the strange

ways and names of this island…

the rough and proud to Boldness and Blackness;

the painful chains to Bad Times;

…he’ll know the haunting that takes you

through Duppy Gate; the slow that goes to Wait-a-Bit;

the correct etiquette to Accompong, even to

Me-No-Sen-You-No-Come…

Excerpt from ‘ ix. in which the cartographer travels lengths and breadths’ by Kei Miller

But we don’t even need to get that deep when the author herself, within the first few pages, breaks the “post racial” illusion by naming whiteness.

“Her best friend, Sesame, had told her that old-time white people had washed their thin hair every day, but nobody had hair like that anymore on Bajacu. You could be arrested for having the kind of stubble Bibi was pointing out. You would certainly be antisocial and have your water ration reduced.”

The above passage made me imagine Bibi and Sorrel, her daughter, as Black because we all know whose hair in the Caribbean gets policed albeit for reasons other than water rations. However, the line about white folx “thin hair” confused me. Why was this assigned to them as an exclusive feature? I started to wonder when the author would acknowledge the existence of Indian and Chinese Jamaicans in some way.

In a later section:

“Cities drowned. The forests fell, the trees simply fell over when the earth couldn’t hold them. The soil washed off and turned the sea grey. The white people, the rich people, left in panicked migration for the north.”

The last sentence is ambiguous, but I decided to be gracious and assume it described two different, if not mutually exclusive, groups. I still had questions. Why did McCaulay go through the effort to name one group racially and not the other, however mixed? These passages established what never changed: the novel’s strange racial binary between whiteness and a nameless other. To accept McCaulay’s “post racial” framing, to assume the characters reference a “long lost before” in their 2084 present when such categories are sapped of all meaning, did nothing to change that binary.

What did that nameless other look like? McCaulay rarely ever described skin complexion; instead, she focused on body type, hair texture, hair length, and eye colour. Her vision of “post racial brown” was red curly hair, or black, straight and long, perhaps “floppy” with most eye colours some “light-eyed” variation. Of the rare times she dared to include skin colour in this vision it was “pale and freckled”, except in one notable instance. The brutal Colonel Drax, unseen for most of the book, was all terrible: he raped, tortured, and maimed the enslaved women under his power. (Yes, she did.) McCaulay detailed Drax’s bald head and stocky figure, the rest left to the imagination. What she described was his brother, “dark-skinned”.

There you have it. Here is a “post racial” brown to fulfill the Jamaican dream of aspirational browness— physical features that pointed to what we would typically place as something other than African. This brown did not know dainty kayah nor the lowly, most popular eye colour amongst all races in the world—brown. The reader could fill those details in, but they were not what the author chose for explicit description. Dark skin met that unknown criteria for notice only when it was in proximity to destructive violence.

Authors, from Toni Morrison to Mariam Qahtani, have shared how they write for the reader as co-creator. In Qahtani’s words, the reader who is “open, interactive, curious, and imaginative. They can fill gaps, find symbols, and appreciate the context.” Daylight Come’s setting can only work as “post racial” for the reader who is passive or oblivious (wilfully or otherwise). They are a reader who will accept, without question, that in the Caribbean an accelerated ecological disaster and the end of racism will happen in the same timeline, on the same trajectory, even though both have the exact same origin story; when analysts predict that the climate crisis will exacerbate such divisions. They cannot know about the Jamaican brown class which operates at the top of the racial hierarchy here, so much say that others call them “white” in recognition of that position, whether or not the person fits the assumed profile in any substantial way.

I read Daylight Come as part of the SOULar Powered Slow Reading Group. Njeri, the group’s founder, asked us as readers to reconsider what may appear as plot holes as “portals of interrogation”: a beautiful regenerative framing. I put this to the author who, I think, needs this prompt as much if not more than her audience. To provide a glimpse of a “post racial” world in a Caribbean place the writer must face head on what she and her audience will bring to the text and incorporate that into how she constructs the story. She cannot craft with the lie that setting it in the future will free her from that reality. She cannot cherry pick complex, ongoing phenomenon with such simplistic fabulation. In McCaulay’s contribution to Annalee Davis’ ‘White Creole Conversations’ project, she wrote about having to face the reality that her ancestors here were slave owners and slaves. She could no longer rest in the false comfort that they were only Baptist missionaries. No doubt that is an ongoing reckoning, but I fear she and Daylight Come appear to exist in two different timelines.

On this island things fidget.

Even history.

Even future.

Works Cited

Miller, Kei. The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion. Carcanet Press, 2014.

Anderson, Jennifer L. Mahogany: The Costs of Luxury in Early America. Harvard University Press, 2012.

Rebel Women Lit. “Like a Real Book Club: The One With Diana McCaulay on ‘Daylight Come,’” October 31, 2020. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.rebelwomenlit.com/podcast/like-a-real-book-club-episode-11-verandah-chat-and-reading-with-diana-mccaulay-author-of-daylight-come.

Contributors to Wikimedia projects. “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song).” Wikipedia, Accessed May 15, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Day-O_(The_Banana_Boat_Song).

Tin House and David Naimon. “Crafting with Ursula: Isaac Yuen on Writing Nature & Nature Writing,” March 10, 2022. Accessed May 8, 2022. https://tinhouse.com/podcast/crafting-with-ursula-isaac-yuen-on-writing-nature-nature-writing/.

Annalee Davis. “White Creole Conversations - Diana McCaulay: Conversations with My Ancestors.” Accessed May 11, 2022. https://annaleedavis.com/diana-mccaulay.

Akilah White is a Jamaican freelance book and film reviewer as well as a sensitivity reader living in the shark's mouth. Her literary writing is in The Book Slut, Rebel Women Lit Magazine, Inklette Magazine, and the Jamaica Gleaner amongst other venues. Her film writing is in Flick Magazine and the upcoming anthology Divergent Terror: The Crossroads of Queerness and Horror (Off Limits Press). When not doom scrolling on Twitter, she bookstagrams at @ifthisisparadise.